It’s the late 1990s. You’re diligently typing up a school project or an important work document on your PC, perhaps running Windows 98 here in India. Suddenly, interrupting your flow, a small, animated paperclip with googly eyes materializes in the corner of your Microsoft Word window. “It looks like you’re writing a letter,” it pipes up in a dialogue box. “Would you like help?” This is Clippit, universally known as Clippy, the Microsoft Office Assistant. Your first reaction might be mild amusement or curiosity. Clippy wasn’t just a feature; it was an interruption, a digital busybody. It aimed to be helpful, maybe even iconic, but instead became a punchline – the poster child for a whole generation of Forgotten tech mascots that tried, and often failed, to win our hearts.

But soon, as Clippy relentlessly offers unsolicited advice, wiggles suggestively when idle, and taps on the screen for attention, that novelty curdles into pure, unadulterated annoyance.

The Pixelated Pioneers (1980s – Early 1990s): “Sprites & Early Concepts”

In the early days of personal computing, mascots weren’t really a major focus for most software and hardware companies, especially outside the vibrant world of video gaming where characters like Mario were already becoming superstars. The focus was on functionality, getting the hardware to work, and navigating complex command-line interfaces or early GUIs. Branding often relied on logos, not characters.

However, there were exceptions and early experiments. Some educational software featured simple characters to guide children. And then there were curiosities like Dr. Sbaitso. Bundled with Creative Labs’ popular Sound Blaster sound cards in the early 1990s, Dr. Sbaitso (an acronym for Sound Blaster Acting Intelligent Text-to-Speech Operator) was an early AI chatbot.

It presented itself as a psychologist, inviting users to type in their problems. Its main purpose was showcasing the card’s text-to-speech capabilities. However, its actual conversational ability was extremely limited, often resorting to canned, repetitive phrases like “WHY DO YOU FEEL THAT WAY?” or “THAT’S NOT MY PROBLEM.” While primitive and hardly a ‘mascot’ in the branding sense, Dr. Sbaitso was an early, memorable character interaction for many PC users, demonstrating technology’s attempt to simulate personality.

Tech Spotlight: Dr. Sbaitso

- Platform: MS-DOS, bundled with Creative Labs Sound Blaster cards (early 1990s).

- Functionality: Early AI chatbot simulating a psychologist, primarily designed to demonstrate text-to-speech synthesis (using First Byte’s “Monologue” engine).

- Interaction: Typed text input, synthesized voice output. Known for repetitive, often unhelpful responses. Would “crash” with a PARITY ERROR if users swore excessively.

- Legacy: Remembered as a quirky, early example of AI interaction and synthesized speech on PCs, pre-dating more sophisticated chatbots.

- Significance: Showcased sound card capabilities through a character interaction, hinting at future digital assistants, albeit in a very rudimentary form.

Milestone Markers

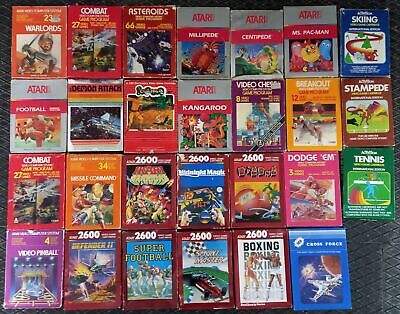

- 1980s: Gaming mascots (Mario, Pac-Man) achieve icon status, while non-gaming tech largely focuses on logos/branding.

- Early 1990s: Educational software sometimes uses simple characters.

- 1991 (late): Creative Labs bundles Dr. Sbaitso with Sound Blaster cards.

Parallel Developments

- 1980s: Rise of the IBM PC compatible standard. MS-DOS dominates. Apple Macintosh introduces the GUI mainstream.

- Early 1990s: Windows 3.x gains traction. Sound cards become essential for multimedia and gaming. The concept of Artificial Intelligence is largely academic or science fiction for consumers.

User Experience Snapshot

Imagine typing your deepest thoughts (or just messing around) into a DOS program, only to have a robotic voice respond with simplistic, detached questions. Dr. Sbaitso wasn’t helpful, but it was novel. It was a voice coming out of your computer, interacting with you, however crudely. It was less a character and more a tech demo given a persona.

Price Point Perspective

Dr. Sbaitso wasn’t sold separately; it was free software bundled with the purchase of a Sound Blaster card (which itself cost a significant amount, but was a popular upgrade). Its value was in demonstrating the hardware’s features.

What We Gained / What We Lost

- Gained: Early exposure to text-to-speech and rudimentary AI chat concepts for many PC users. A quirky footnote in tech history.

- Lost: Nothing – it was bonus software.

Unexpected Consequences

- Became a nostalgic touchstone for those who grew up with early Sound Blaster cards.

- Possibly demonstrated the limitations and potential annoyance factor of early AI interaction.

Industry Voice

“HELLO [UserName], MY NAME IS DOCTOR SBAITSO. I AM HERE TO HELP YOU. SAY WHATEVER IS IN YOUR MIND FREELY…” – Dr. Sbaitso’s opening lines.

The Assistant Uprising (Mid-1990s – Early 2000s): “Your Digital ‘Helpers'”

This era saw a concerted effort by tech companies, particularly Microsoft, to make increasingly complex software feel more user-friendly by introducing anthropomorphic “assistants.” The intention was noble; the execution, often disastrously annoying.

The undisputed king of this era was Clippit, aka Clippy, the googly-eyed paperclip introduced in Microsoft Office 97. Designed by Kevan J. Atteberry and based on Stanford research suggesting people react emotionally to computers as they do to people, Clippy (and other selectable assistants like “The Dot” or “The Genius”) was supposed to proactively offer help.

Unfortunately, its suggestions were often contextually wrong, its animations intrusive, and its mere presence became infuriating for millions trying to focus on their work. Clippy wasn’t just unhelpful; it felt patronizing.

Clippy was actually a descendant of an even more ambitious failure: Microsoft Bob (1995-1996). Bob was an attempt to replace the standard Windows interface with a virtual “house” where rooms represented functions and cartoon characters acted as guides.

Characters like Rover the friendly dog, Scuzz the rat, or Shelly the turtle were meant to make computing intuitive for novices. Instead, users found Bob slow, confusing, resource-hungry, and overly simplistic. It flopped commercially but left two unfortunate legacies: the technology that would become the Office Assistants (like Clippy), and the much-maligned font Comic Sans, created specifically for Bob.

This era also saw the rise (and fall) of BonziBuddy, a free downloadable desktop assistant in the form of a purple gorilla (later other characters). BonziBuddy could talk, tell jokes, manage downloads, and more. However, it quickly gained notoriety for displaying intrusive ads, tracking user behavior, and bundling adware and spyware. It became less a helpful mascot and more a piece of malware, eventually leading to lawsuits and its demise.

Tech Spotlight: Microsoft Agent & Desktop Assistants

- Technology: Microsoft Agent (underlying tech for Clippy) allowed animated characters with synthesized speech or recorded audio to interact with users. Microsoft Bob used a “social interface” metaphor. BonziBuddy used early agent technology combined with adware/spyware tactics.

- Goal: To provide proactive help, make interfaces seem friendlier, guide novice users.

- User Reaction: Generally negative. Assistants were seen as annoying, intrusive, unhelpful, patronizing (Clippy, Bob), or malicious (BonziBuddy).

- Examples: Clippit/Clippy & other Office Assistants (Office 97-2003), Rover & other Microsoft Bob characters (1995-1996), BonziBuddy (late 90s-early 00s).

- Significance: Represented a major push towards anthropomorphic UI design that largely backfired, teaching valuable lessons about user interaction and the limits of “helpfulness.”

Milestone Markers

- 1995: Microsoft Bob launches and quickly fails.

- 1996: Microsoft Bob is discontinued.

- 1997: Microsoft Office 97 introduces Clippy and the Office Assistants.

- Late 1990s: BonziBuddy appears and gains notoriety.

- 2001: Microsoft begins phasing out Clippy with Office XP, even running humorous ad campaigns featuring a fired Clippy (voiced by Gilbert Gottfried) begging for his job back.

- 2007: Office Assistants removed entirely from Microsoft Office.

Parallel Developments

- Mid-Late 1990s: Windows 95/98 become dominant. Internet Explorer battles Netscape. The internet boom leads to more non-technical users getting online. Usability and user experience become increasingly important design considerations.

User Experience Snapshot

Do you remember desperately trying to disable Clippy? The sheer frustration when it popped up for the hundredth time while you were just trying to type “Dear Sir”? Or maybe you encountered Microsoft Bob on a display computer and wondered who thought this was a good idea?

And perhaps a less tech-savvy relative installed BonziBuddy, leading to a computer overwhelmed with pop-up ads? This era wasn’t just about using software; it was often about battling the annoying characters trying to “help” you use it.

Price Point Perspective

Clippy and Bob were part of the cost of Microsoft Office or Windows. BonziBuddy was “free,” but the hidden cost was adware, spyware, and system performance degradation. The cost here was often measured in user sanity and lost productivity.

What We Gained / What We Lost

- Gained: Valuable lessons in UI design (less is often more). A cultural icon of annoyance (Clippy). Enduring memes (Clippy, Comic Sans).

- Lost: The dream of truly helpful, unobtrusive AI assistants (at least for a while). User trust, in the case of BonziBuddy. Countless hours of user productivity battling unwanted “help.”

Unexpected Consequences

- Clippy’s failure profoundly influenced UI design, leading to more subtle, user-initiated help systems.

- Microsoft Bob became a case study in failed software design and misunderstanding user needs.

- BonziBuddy served as an early, high-profile example of the dangers of seemingly harmless free downloads.

Industry Voice

“Microsoft’s Bob was a cartoon interface designed to be easy to use for new computer users. But everyone hated poor Bob… Not only was the interface slower and more confusing than regular Windows, but the cutesy cartoons were annoying.” – Museum of Failure.

The Web & Brand Ambassadors (Late 1990s – Mid 2000s): “Faces of the Early Internet”

[ERA IMAGE SUGGESTION: The original Ask Jeeves website interface featuring the butler mascot, side-by-side with the Netscape ‘N’ logo featuring the Mozilla lizard.]

As the World Wide Web took center stage, companies building online services and software also experimented with mascots to create brand identity and guide users through the often-chaotic early internet.

One of the most recognizable figures was Jeeves, the quintessential English butler mascot for the search engine Ask Jeeves (launched 1996/97). Based on P.G. Wodehouse’s famous character, Jeeves personified the site’s concept: allowing users to ask questions in natural language and receive answers “fetched” by the helpful valet.

The portly, knowledgeable butler was ubiquitous in Ask Jeeves branding and advertising (even appearing on fruit stickers and as a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloon) until 2006, when the company rebranded to Ask.com and retired the character (though he briefly reappeared in the UK). Jeeves represented an attempt to make web search feel like a personalized service.

Another notable, though perhaps more abstract, mascot was Mozilla, associated with the Netscape Navigator browser. Initially a codename for the project (“Mosaic killer”), Mozilla took the form of a green, Godzilla-like lizard designed by Dave Titus in 1994, appearing on Netscape’s early website and internal materials.

It embodied the company’s aggressive ambition. Later, when the Mozilla open-source project launched (1998), Shepard Fairey redesigned the mascot as a fiercer, red T-Rex. While never as interactive as Clippy, Mozilla served as a visual symbol for the pioneering browser and the subsequent open-source movement, before eventually being retired from official branding in favor of wordmarks.

Tech Spotlight: Web Service Personas

- Concept: Using characters to personify online services, make them seem more approachable, or represent brand values.

- Interaction: Usually non-interactive branding elements, though Jeeves implied an interactive Q&A function.

- Goal: Brand recognition, conveying service purpose (Jeeves as helpful answer-provider), embodying company spirit (Mozilla as competitor).

- Examples: Jeeves the butler (Ask Jeeves, 1996-2006), Mozilla the lizard/dinosaur (Netscape/Mozilla, mid-90s onwards, retired ~2012).

- Significance: Showed attempts to give abstract online services a relatable face during the early web era, influencing web branding strategies.

Milestone Markers

- 1994: Netscape Navigator launches, initially featuring the green Mozilla mascot internally and on early web materials.

- 1996/1997: Ask Jeeves search engine launches featuring the Jeeves butler mascot.

- 1998: Mozilla open-source project launches, later adopting a redesigned red dinosaur mascot.

- 2006: Ask Jeeves rebrands to Ask.com and officially retires the Jeeves character in most markets.

- ~2012: Mozilla project retires the dinosaur mascot from official branding.

Parallel Developments

- Late 1990s: The “Browser Wars” between Netscape Navigator and Internet Explorer. The Dot-com boom peaks. Search engines (AltaVista, Yahoo!, Google) compete for dominance.

- Early 2000s: Google establishes dominance in search. Web 2.0 concepts begin to emerge.

User Experience Snapshot

Remember typing questions into Ask Jeeves and seeing the butler graphic, feeling like you were interacting with a helpful assistant rather than just a search algorithm? Or seeing the Netscape ‘N’ throb with the Mozilla lizard animation while a page loaded? These characters added a touch of personality to the often-sterile interfaces of the early web, making brands more memorable, even if their direct utility varied.

Price Point Perspective

These mascots were associated with free web services (search engines, browsers). Their value was in branding and user engagement, not direct monetization related to the character itself.

What We Gained / What We Lost

- Gained: Memorable branding for early web services. Attempts to make technology feel more human and approachable.

- Lost: The mascots themselves as companies rebranded or shifted strategy. The specific Q&A approach personified by Jeeves eventually faded in mainstream search.

Unexpected Consequences

- The Jeeves character became strongly associated with the Ask brand, perhaps making the later rebranding more difficult.

- The Mozilla mascot’s legacy lives on in the name of the foundation and browser, even after the character itself was retired.

Industry Voice

“The company’s cartoon mascot, a portly butler based on the English valet in P.G. Wodehouse novels, was a ubiquitous fixture on the Internet by the end of the 1990s.” – Encyclopedia.com (On Ask Jeeves).

The Gaming Graveyard (Various Eras): “Mascots Who Missed the High Score”

[ERA IMAGE SUGGESTION: A composite image showing Alex Kidd, Polygon Man, and Blinx looking slightly forlorn or faded.]

The video game industry is littered with iconic mascots – Mario, Sonic, Pac-Man, Master Chief. But for every success story, there are characters designed to be platform figureheads who stumbled, faded, or were quickly overshadowed. These are the almost-icons of the console wars.

Before Sonic the Hedgehog arrived with his blazing speed and attitude, Sega’s primary mascot was Alex Kidd. Debuting in Alex Kidd in Miracle World (1986) for the Master System, the big-eared, jumpsuit-wearing character starred in several games.

Originally conceived during development of a Dragon Ball game adaptation, Alex was Sega’s answer to Mario. However, his games were inconsistent in quality and style (ranging from platforming to BMX racing), and his design lacked the edgy coolness Sega later embraced. When Sonic debuted in 1991, Alex Kidd was quickly relegated to history, becoming an emblem of Sega’s pre-Sonic era.

Sony’s original PlayStation (PSX) also had a fleeting, bizarre mascot attempt: Polygon Man. This disembodied, angular, purple head was used in early North American marketing and tech demos before the console’s launch in 1995.

Meant to showcase the power of 3D polygons, he was reportedly disliked by Sony executives (including Ken Kutaragi, the “Father of PlayStation”) and was swiftly dropped, never becoming the official face of the brand. He later reappeared as the final boss in the 2012 game PlayStation All-Stars Battle Royale, a nod to his obscure origins.

Even Microsoft tried to create a non-Master Chief mascot for the original Xbox. Blinx the Time Sweeper (2002) starred an anthropomorphic cat who could manipulate time. Developed by Artoon (founded by Sonic co-creator Naoto Ohshima), Blinx was explicitly intended as an Xbox-exclusive mascot to compete with Mario, Sonic, and Sony’s Ratchet & Clank.

While the game received mixed reviews and even a sequel (Blinx 2: Masters of Time and Space, 2004), the character never achieved widespread popularity or the iconic status Microsoft hoped for, fading away as Master Chief became the undisputed face of Xbox.

Tech Spotlight: Platform-Exclusive Characters

- Goal: Create unique, appealing characters to represent a specific console brand, drive hardware sales, and compete with rival mascots (primarily Mario and Sonic).

- Strategy: Feature the character in exclusive launch titles or flagship games showcasing the console’s capabilities.

- Outcome: Often failed due to inconsistent game quality, unappealing character design, changing market tastes, or being overshadowed by characters from more successful third-party or first-party games (like Master Chief).

- Examples: Alex Kidd (Sega Master System, 1986-1990), Polygon Man (Pre-launch PlayStation, ~1994-1995), Blinx the Time Sweeper (Xbox, 2002-2004).

- Significance: Illustrates the high stakes and difficulty of creating successful, enduring mascots in the competitive console market. Many were called, few were chosen.

Milestone Markers

- 1986: Alex Kidd in Miracle World launches on Sega Master System.

- 1991: Sonic the Hedgehog launches, effectively replacing Alex Kidd as Sega’s mascot.

- ~1995: Polygon Man used in pre-launch PlayStation marketing, then dropped.

- 2001: Halo: Combat Evolved launches with Xbox, establishing Master Chief.

- 2002: Blinx: The Time Sweeper launches as an intended Xbox mascot.

- 2004: Blinx 2 released, marks the end of the character’s run.

Parallel Developments

- Late 1980s: 8-bit console war (NES vs. Master System).

- 1990s: 16-bit war (SNES vs. Genesis/Mega Drive), transition to 3D (PlayStation, N64, Saturn).

- Early 2000s: 6th generation consoles (PS2, Xbox, GameCube). Rise of FPS genre on consoles.

User Experience Snapshot

Maybe you owned a Master System and have fond memories of Alex Kidd’s rock-paper-scissors boss battles. Perhaps you saw Polygon Man in an old magazine ad and wondered what that strange purple head was about. Or you might have played Blinx on the original Xbox, enjoying the time mechanics but not quite connecting with the character. These mascots represent roads not taken, alternative faces for consoles that ultimately found their identity elsewhere.

Price Point Perspective

These characters were intrinsically tied to the cost of their respective games and consoles. Their success or failure directly impacted the perceived value and appeal of the hardware they represented.

What We Gained / What We Lost

- Gained: Some interesting (if flawed) games featuring these characters. Insight into console manufacturers’ early branding strategies. A graveyard of “what might have been” mascots.

- Lost: The potential franchises and iconic status these characters never achieved.

Unexpected Consequences

- The failure of earlier attempts arguably made the success of later mascots (like Sonic or Master Chief) even more impactful.

- These forgotten characters sometimes gain cult followings or reappear as Easter eggs or trivia references (like Polygon Man).

Industry Voice

“Alex Kidd was the mascot that Sega envisioned to take on Nintendo’s trusty plumber, but he simply didn’t cut the mustard… Kidd would be consigned to the dustbin of video game history…” – CBR.com (On Alex Kidd’s fate). “Blinx was intended to be a mascot character for Microsoft to use to compete against Nintendo’s Mario, Sega’s Sonic the Hedgehog and Sony’s Ratchet…” – Wikipedia (On Blinx’s ambitious goal).

Why They Vanished: “Logging Off Forever”

Why did Clippy, Jeeves, Alex Kidd, and countless others fade into obscurity while Mario, Sonic, and the Android robot endure? There’s no single reason, but several factors contributed to the mascot graveyard:

- Annoyance Factor: Characters designed to be “helpful,” like Clippy or BonziBuddy, often became intensely irritating. Proactive, unsolicited advice and intrusive animations actively hindered user experience, leading to backlash.

- Poor Design/Concept: Some mascots just weren’t appealing or well-conceived. Microsoft Bob’s entire social interface felt condescending and inefficient. Alex Kidd’s design and gameplay lacked the focus and “cool factor” of Sonic. Polygon Man was just… weird.

- Shifting UI Paradigms: As software interfaces became more intuitive and online help resources (FAQs, forums, search engines) improved, the need for built-in, anthropomorphic assistants diminished. They felt like relics of an earlier, clunkier era.

- Product Failure/Strategy Shifts: Mascots tied to unsuccessful products (Microsoft Bob) naturally disappeared. Companies also rebranded or changed strategic direction, leaving mascots behind (Ask Jeeves becoming Ask.com, Netscape being replaced by Firefox which adopted a different logo).

- Being Overshadowed: Many platform mascots, like Alex Kidd or Blinx, simply couldn’t compete with more popular characters emerging from hit games on their own or competing platforms. Master Chief became the face of Xbox organically, not by design like Blinx.

- Malware/Negative Associations: Characters like BonziBuddy became synonymous with spyware and adware, leading to their eradication for security reasons.

- Lack of Cultural Resonance: Ultimately, creating an enduring icon requires more than just a cute character. It needs consistent quality, cultural relevance, and a genuine connection with the audience – a difficult feat that most tech mascots simply failed to achieve.

Full Circle Reflections

The path to tech icon status is littered with forgotten faces. From awkward early AI experiments like Dr. Sbaitso, through the universally loathed helpfulness of Clippy, the polite servitude of Jeeves, and the failed ambitions of would-be console stars like Alex Kidd, the history of tech mascots is a fascinating journey through design trends, branding strategies, and the often-hilarious missteps in trying to give technology a friendly face.

These characters, even the annoying ones, were products of their time. They represented attempts – sometimes clumsy, sometimes misguided – to bridge the gap between complex technology and everyday users, to build brand loyalty, or to simply stand out in a crowded market. While most failed to achieve lasting fame, they haven’t entirely vanished.

They live on in our nostalgic memories, in internet memes, and as cautionary tales in design textbooks. They are the almost-icons, the digital ghosts reminding us of past interfaces and the enduring challenge of creating characters that truly connect.

The Heritage Impact: Lessons from the Lost

The forgotten mascots left their mark, often by teaching valuable lessons:

- User Experience is King: Annoying or intrusive features, no matter how well-intentioned, will alienate users (Clippy Principle).

- Authenticity Matters: Forced personality or overly simplistic interfaces can feel condescending (Microsoft Bob).

- Simplicity Can Win: Enduring mascots often have strong, simple designs and clear associations (vs. the inconsistency of Alex Kidd).

- Context is Crucial: A mascot fitting for one era or purpose may not translate to another (Jeeves in the age of Google).

- Organic Growth > Forced Fame: Often, the most beloved characters emerge organically from successful products rather than being designed top-down as brand ambassadors (Master Chief vs. Blinx).

These digital ghosts, in their failure, helped shape the more streamlined, less intrusive, and arguably less quirky tech landscape we navigate today.

FAQ: Remembering the Almost-Icons

- Who was Clippy the paperclip?

Clippy (officially Clippit) was an animated Office Assistant in Microsoft Office versions from Office 97 to Office 2003. It was designed to proactively offer help but became infamous for being annoying and intrusive. - What happened to the butler from Ask Jeeves?

Jeeves, the butler mascot for the Ask Jeeves search engine (launched 1996/97), was officially retired in most markets in 2006 when the company rebranded to Ask.com and shifted its focus away from the Q&A persona. - What was Microsoft Bob?

Microsoft Bob (1995-1996) was a short-lived graphical user interface intended to replace the Windows Program Manager. It used a “virtual house” metaphor with cartoon characters (like Rover the dog) as guides. It failed due to being confusing, slow, and poorly received by users. - Why did tech companies create mascots?

Companies used mascots for various reasons: to make their brand more memorable and approachable, to personify complex software or services, to guide users (like Office Assistants), or to create a recognizable face for a platform (like console mascots). - Are there any successful non-gaming tech mascots?

Yes, though fewer achieve the fame of gaming icons. The Android robot (often called “Bugdroid”) is globally recognized. Tux, the Linux penguin, is beloved within the open-source community. Arguably, GitHub’s Octocat has also become quite recognizable in developer circles.