Picture this: It’s the early 1990s. You’re sitting in front of a beige computer, maybe an early assembled PC common in Indian households or colleges back then, running MS-DOS. You need to send a batch of important Word Perfect documents to a colleague, or perhaps you’ve just downloaded a cool shareware game from a local Bulletin Board System (BBS) spread across several files. The history of ZIP files began in 1989 when Phil Katz developed the ZIP format to compress and archive files efficiently.

The problem? Floppy disks only hold 1.44MB, and your dial-up modem connection crawls at speeds measured in kilobits per second. Transferring multiple files is agonizingly slow, and fitting them all on one disk seems impossible. Then, someone introduces you to a command-line miracle: PKZIP.

You type the arcane command: C:\> pkzip -a files.zip *.wp. After some frantic disk activity and cryptic messages scrolling up the screen, a single, significantly smaller file – FILES.ZIP – appears. It fits on the floppy! The BBS upload takes a fraction of the time! This small utility, born from legal battles and technical brilliance, wasn’t just convenient; it was revolutionary, fundamentally changing how we stored and shared digital information forever.

The Archive Wars (Mid-Late 1980s): “Before the Zip: ARC & The Need for Speed”

Before ZIP zipped onto the scene, the digital world desperately needed ways to shrink files. Hard drives were measured in tens of megabytes and cost a fortune, floppy disks were the primary means of transfer, and modems were painfully slow.

File compression wasn’t a luxury; it was a necessity. In this environment, the ARC format, created by Thom Henderson of System Enhancement Associates (SEA), emerged as a popular standard, especially on BBSs. ARC allowed users to bundle multiple files into a single archive (.ARC) and compress them to save space and download time.

Enter Phil Katz, a brilliant but iconoclastic programmer from Wisconsin. He developed his own ARC-compatible archiver, PKARC, which was significantly faster than SEA’s original. Distributed as shareware, PKARC quickly gained popularity in the tech-savvy BBS community.

This success, however, led to conflict. In 1988, SEA sued Katz and his newly formed company, PKWARE, Inc., for copyright and trademark infringement, claiming PKARC was a derivative work of ARC. An independent expert compared the code and found significant overlap, including identical comments and even spelling errors. SEA won the lawsuit.

The settlement forced Katz to stop distributing ARC-compatible software after January 1989 and pay damages. While a legal victory for SEA, it sparked outrage in the BBS community, who largely sided with Katz, viewing him as the innovative underdog battling a corporation. This set the stage for Katz’s next move.

Tech Spotlight: The ARC Format

- Creator: System Enhancement Associates (SEA), Thom Henderson.

- Functionality: Bundled multiple files into a single archive (.ARC) with compression (using variations of Lempel-Ziv).

- Popularity: Became the de facto standard on BBSs in the mid-to-late 1980s.

- Downfall: Superseded rapidly by ZIP following the SEA vs. PKWARE lawsuit and the perceived advantages of PKZIP.

- Significance: Popularized the concept of combined archiving and compression for personal computers, highlighting the need for efficient file management.

Milestone Markers

- Mid-1980s: ARC format gains widespread use on BBSs.

- ~1986: Phil Katz releases PKARC, a faster ARC-compatible archiver.

- 1988: SEA files lawsuit against PKWARE and Phil Katz. Settlement reached, forcing PKWARE to cease distributing ARC-compatible programs.

Parallel Developments

- Mid-Late 1980s: BBS culture thrives as the primary online community space. Shareware software distribution model gains traction. PCs become more powerful, but storage and modem speeds remain limited.

User Experience Snapshot

Using ARC felt essential. If you were downloading files from a BBS, they were almost certainly .ARC archives. You needed the right utility (ARC or PKARC) to extract them. Compression ratios were decent for the time, noticeably reducing download times compared to uncompressed files, but Katz’s faster PKARC quickly became the preferred tool for many, sowing the seeds of the coming standard shift.

Price Point Perspective

Both ARC and PKARC were initially distributed using the shareware model. Users could try the software for free, but were expected to pay a registration fee (e.g., around $20-$40) for continued use or additional features/manuals. The primary value was in saved time (downloads) and disk space.

What We Gained / What We Lost

- Gained: A widely adopted standard for archiving and compression (ARC). Proof of the market demand for faster, more efficient tools (PKARC).

- Lost: The ARC format’s dominance due to the lawsuit’s fallout and the subsequent rise of ZIP.

Unexpected Consequences

- The lawsuit galvanized the BBS community, creating immense goodwill for Phil Katz and PKWARE.

- Set a precedent (though controversial) regarding derivative works in software development.

- Created the market vacuum that ZIP would perfectly fill.

Industry Voice

“[The lawsuit was] widely regarded by the BBS community as being a ‘David vs. Goliath’ case… though in fact both companies were small, home-based operations.” – FileFormat.Info Wiki (on the perception of the SEA vs PKWARE case).

The PKZIP Revolution (1989 – Early 1990s): “Unzipping a New Standard”

Forced to abandon ARC, Phil Katz didn’t just retreat; he innovated. In 1989, PKWARE released PKZIP, a new archiving utility built around the brand new .ZIP file format. Crucially, Katz, along with Gary Conway of Infinity Design Concepts, published the technical specification for the core ZIP format in a file called APPNOTE.TXT, effectively placing much of it in the public domain. This open approach, combined with PKZIP’s technical merits, was key to its explosive success.

PKZIP utilized the DEFLATE algorithm, a clever combination of LZ77 (which finds repeated sequences of data) and Huffman coding (which assigns shorter codes to more frequent symbols). This resulted in compression ratios that were often better than ARC, and the program itself was known for its speed. The name “ZIP,” suggested by Katz’s friend Robert Mahoney, was chosen deliberately to imply this velocity.

Riding the wave of goodwill from the ARC lawsuit and propelled by its technical superiority and open specification, PKZIP (and its counterpart, PKUNZIP) rapidly replaced ARC as the standard on BBSs.

Sysops (System Operators) encouraged users to switch, shareware authors distributed their software in ZIP archives, and users eagerly embraced the faster, more efficient format. PKZIP, the DOS command-line tool, became an essential utility for any serious PC user involved in file sharing or software downloading.

Tech Spotlight: PKZIP & The DEFLATE Algorithm

- Software: PKZIP (compressor) and PKUNZIP (extractor). Command-line utilities for MS-DOS.

- Format: .ZIP – Introduced by PKWARE in 1989. Specification largely published in the public domain (APPNOTE.TXT).

- Algorithm: DEFLATE (combines LZ77 dictionary coding and Huffman statistical coding). Generally offered better compression and speed than ARC’s methods.

- Distribution Model: Shareware (PKZIP registration was required for certain features/licensing, PKUNZIP was often freely distributable).

- Significance: Established the .ZIP format as the new de facto standard for file compression and archiving, rapidly displacing ARC due to technical superiority, an open specification, and community support.

Milestone Markers

- 1989: PKWARE releases PKZIP 1.0 and publishes the initial .ZIP file format specification (APPNOTE.TXT).

- Late 1989 / Early 1990s: ZIP format rapidly adopted by BBSs and shareware authors, becoming the dominant standard.

- Ongoing: PKWARE continues to update PKZIP and the APPNOTE.TXT specification, adding features like encryption (ZipCrypto) and eventually support for newer algorithms (though DEFLATE remains the core).

Parallel Developments

- Early 1990s: Continued growth of BBSs. Early commercial internet access begins. Windows 3.x starts gaining popularity but DOS remains prevalent for many tasks. Shareware distribution peaks.

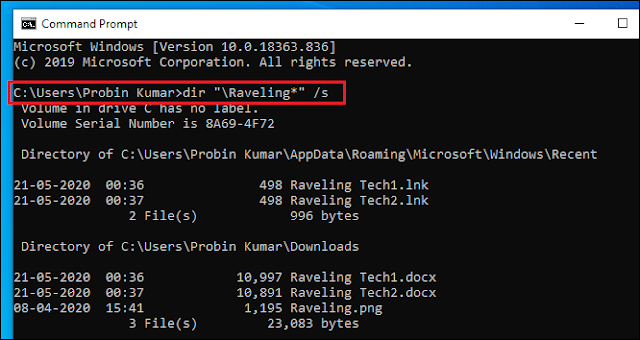

User Experience Snapshot

Learning the PKZIP commands felt like mastering a secret handshake. pkzip -a myfiles *.txt (add all text files to myfiles.zip), pkunzip stuff.zip c:\temp (extract stuff.zip to the temp directory). It required typing precise commands, but the results were immediate and satisfying: files shrank significantly, fitting onto floppies or transferring much faster over slow modems. Watching the percentage counter tick up during compression or extraction was a familiar sight. For tech-savvy users, PKZIP was fast, reliable, and empowering.

Price Point Perspective

PKZIP continued the shareware model ($25-$47 registration depending on manual). The value proposition remained strong: saving disk space (still expensive) and dramatically reducing modem transfer times (often charged by the minute) easily justified the cost for frequent users. PKUNZIP was generally free to distribute, ensuring everyone could extract archives.

What We Gained / What We Lost

- Gained: A faster, more efficient, and largely open compression standard (ZIP/DEFLATE). A unified format that quickly gained universal acceptance in online communities. Powerful command-line tools.

- Lost: The ARC format faded into obscurity. Fragmentation during the brief transition period.

Unexpected Consequences

- The open nature of the ZIP specification allowed countless other developers to create compatible archivers and extractors, cementing its ubiquity.

- Phil Katz became a legendary, albeit controversial, figure in the software world.

- Established a baseline expectation for compression performance that spurred further innovation.

Industry Voice

“The name ‘zip’ (meaning ‘move at high speed’) was suggested by Katz’s friend, Robert Mahoney. They wanted to imply that their product would be faster than ARC and other compression formats of the time.” – Wikipedia (on the origin of the name).

The Windows Wrapper (Mid-1990s – Early 2000s): “Making Zip Click: WinZip & the GUI”

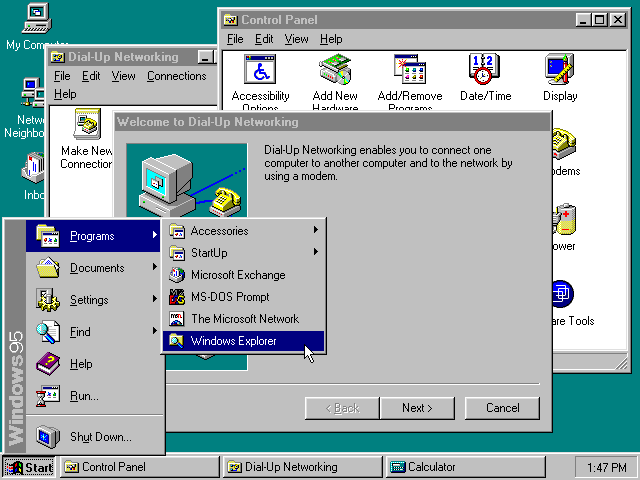

While PKZIP dominated the DOS command line, the computing world was shifting towards graphical user interfaces (GUIs), primarily Microsoft Windows. Typing arcane commands felt increasingly user-unfriendly for the average person adopting Windows 95. This created an opportunity for a more accessible way to handle the now-standard ZIP files.

Enter WinZip. Initially developed by Nico Mak and released in 1991, early versions of WinZip were essentially GUI “shells” or front-ends that worked with PKZIP and PKUNZIP. Instead of typing commands, users could now drag and drop files, click buttons to compress or extract, and browse the contents of archives visually. This intuitive interface made the power of ZIP compression accessible to millions of non-technical Windows users.

WinZip, distributed as shareware like its command-line predecessor, became incredibly popular, almost synonymous with ZIP files on the Windows platform. Over time, WinZip evolved, incorporating its own compression code licensed from the Info-ZIP group and adding support for other archive formats, but its initial success was built on making PKZIP’s functionality easy to use. Other GUI archivers also emerged during this period, notably WinRAR (released 1995), which introduced its own efficient proprietary RAR format but also handled ZIP files adeptly. This era cemented ZIP’s dominance by making it effortless to use within the world’s most popular operating system.

Tech Spotlight: WinZip (Graphical User Interface)

- Creator: Nico Mak (initially), WinZip Computing.

- Functionality: Provided a user-friendly graphical interface for creating, extracting, and managing ZIP archives on Windows. Initially acted as a shell for PKZIP/PKUNZIP, later integrated its own compression engine.

- Impact: Massively popularized ZIP files beyond the tech-savvy BBS/DOS users by making compression accessible through an intuitive GUI. Became the dominant ZIP utility for Windows for many years.

- Distribution Model: Shareware (long evaluation periods made it almost freeware for many).

- Significance: Bridged the gap between the powerful command-line PKZIP and the average Windows user, cementing ZIP’s ubiquity by making it easy.

Milestone Markers

- 1991: WinZip first released by Nico Mak Computing.

- 1995: Windows 95 launches, driving mass adoption of GUIs. WinZip’s popularity surges. WinRAR is also released.

- Mid-late 1990s: WinZip becomes the de facto standard GUI tool for handling ZIP files on Windows.

- Early 2000s: WinZip continues to add features and support for newer ZIP extensions.

Parallel Developments

- Mid-1990s: Widespread adoption of Windows 95. The internet and World Wide Web explode in popularity. CD-ROMs become standard PC components.

- Late 1990s: Email becomes a primary communication tool. Downloading software from websites begins to compete with physical media and shareware distribution.

User Experience Snapshot

Do you remember installing WinZip (often from a magazine cover disc!) and suddenly feeling like a compression expert? Dragging files onto the WinZip window, clicking “Add,” and watching the archive build? Double-clicking a ZIP file and seeing its contents appear in a neat list, ready to be extracted with another click? It felt intuitive, powerful, and infinitely easier than memorizing PKZIP command switches. WinZip made handling ZIP files a simple, everyday task for millions.

Price Point Perspective

WinZip’s shareware model meant users could try it extensively for free, though registration (around $29 USD) was required for long-term use and full features. Its perceived value was immense, saving users time and hassle compared to command-line tools or dealing with uncompressed files.

What We Gained / What We Lost

- Gained: Easy-to-use graphical interface for ZIP files, making compression accessible to everyone. Solidified ZIP as the cross-platform standard. Increased productivity for managing files.

- Lost: Reliance on command-line proficiency for basic compression tasks faded.

Unexpected Consequences

- WinZip’s success demonstrated the huge market for user-friendly utilities that simplify complex tasks.

- The familiarity of the WinZip interface influenced how operating systems would later integrate ZIP functionality.

- Created brand loyalty that persists for many users even after OS integration.

Industry Voice

“WinZip was first released in 1991 by Nico Mak Computing as a graphical user interface (GUI) front-end for the PKZIP command-line utility.” – CIO Wiki (Summarizing WinZip’s origins).

The Internet’s Workhorse (Late 1990s – Mid 2000s): “Shrinking the Web”

As the internet transitioned from a niche network to a global phenomenon, the ZIP format became utterly indispensable. In the era of relatively slow dial-up and early broadband connections, bandwidth was a precious commodity. ZIP wasn’t just convenient; it was the essential workhorse that made sharing information online practical.

Virtually all software distributed online – whether full applications, shareware, drivers, or game patches – was packaged in ZIP archives to reduce download times. Sending multiple photos or documents via email? You’d zip them up first to avoid hitting attachment size limits (which were much smaller then) and make the transfer faster for both sender and receiver. Web developers often bundled website assets (images, scripts) into ZIP files for easier uploading or distribution. FTP sites, the precursors to cloud storage for file sharing, were filled with ZIP archives. The .zip extension became one of the most common sights online. Without the efficiency provided by ZIP and the DEFLATE algorithm, the early internet would have felt significantly slower and more cumbersome.

Tech Spotlight: ZIP as the Internet Standard

- Role: The universal format for distributing compressed files over the internet.

- Applications: Software downloads (applications, shareware, drivers, patches), email attachments (bundling multiple files, reducing size), website asset distribution, general file archiving for transfer via FTP or web download.

- Impact: Made large file transfers feasible over limited bandwidth. Reduced download times significantly. Conserved web server storage space. Became the expected format for nearly all downloadable archived content.

- Significance: Played a critical, foundational role in the growth and usability of the early internet by making file distribution efficient.

Milestone Markers

- Late 1990s: As web usage explodes, ZIP becomes the standard for nearly all online file distribution.

- ~1998-2005: Peak reliance on ZIP for managing internet downloads and email attachments due to bandwidth constraints.

- Early 2000s: Email providers enforce attachment size limits, further cementing the need for ZIP.

Parallel Developments

- Late 1990s: Dot-com boom fuels massive web growth. Email becomes ubiquitous. MP3 format popularizes digital music downloads (often shared, sometimes illegally, in ZIP files).

- Early 2000s: Broadband adoption increases, but speeds are still limited compared to today. Peer-to-peer file sharing networks emerge.

User Experience Snapshot

Remember downloading a crucial driver or a cool shareware game from a website, seeing that .zip extension, and knowing exactly what to do? You’d download the file (watching the progress bar crawl on dial-up), then fire up WinZip (or maybe PKUNZIP if you were old school) to extract the contents. Sending photos to family? Zip ’em up first! It was an automatic, ingrained part of using the internet. Handling ZIP files was a basic digital literacy skill.

Price Point Perspective

The software (PKZIP/WinZip) often had a cost (shareware registration), but the savings came from reduced online time (often charged per minute on dial-up) and fitting within email limits. The efficiency gain far outweighed the software cost for active internet users.

What We Gained / What We Lost

- Gained: A universal, reliable standard for online file distribution. Practical means to share software and multiple files despite bandwidth limits. Faster downloads and uploads.

- Lost: The need to think explicitly about compression faded as it became the default for distributed files.

Unexpected Consequences

- ZIP’s ubiquity made it a target for spreading malware; users learned (sometimes the hard way) to be cautious about opening ZIP files from unknown sources.

- Concepts like “ZIP bombs” (maliciously crafted archives designed to crash extractors) emerged as security threats.

- Reinforced the importance of having a reliable ZIP utility installed on every internet-connected PC.

Industry Voice

“[The ZIP format] compatibility… proliferated widely on the public Internet during the 1990s.” – Wikipedia (On ZIP’s rapid online adoption).

The Integrated Era & Beyond (Late 2000s – Present): “Built-in & Still Relevant”

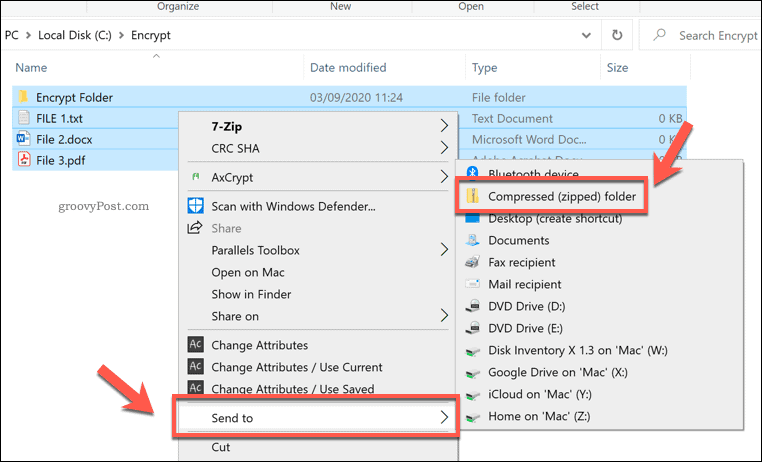

The final major evolution in the ZIP story was its integration directly into operating systems. Recognizing its universal importance, Microsoft added built-in support for creating and extracting ZIP files (initially via the “Plus! 98” add-on, then natively as “Compressed Folders” in Windows ME and Windows XP around 2000-2001). Apple followed suit with macOS (Archive Utility).

This native support meant that for basic tasks – zipping up a few files for an email, or extracting a downloaded archive – users no longer needed a third-party application like WinZip or WinRAR. The functionality was right there in the operating system, usually just a right-click away.

Has this killed dedicated compression utilities? Not entirely. While less essential for basic tasks, tools like WinZip, WinRAR, and the open-source powerhouse 7-Zip remain popular for their advanced features:

- Stronger Encryption: Offering AES encryption, far more secure than traditional ZipCrypto.

- Support for Other Formats: Handling RAR, 7z, TAR, GZ, and many others. (7z often provides significantly better compression ratios than standard ZIP/DEFLATE).

- Advanced Features: Creating self-extracting archives, splitting archives into multiple volumes, repairing damaged archives, deeper integration with cloud services.

Furthermore, while cloud storage (Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive) and significantly faster internet speeds have reduced the absolute necessity of compression for saving space or everyday file sharing for some, ZIP remains incredibly relevant. It’s still the most universally compatible archive format, perfect for bundling multiple files into a single package for email or download, ensuring the recipient can almost certainly open it without special software. It’s simple, effective, and understood everywhere.

Tech Spotlight: OS Integration & Modern Utilities

- OS Integration: Native support for basic ZIP creation/extraction built into Windows (“Compressed Folders”) and macOS (“Archive Utility”). Makes basic ZIP handling seamless without extra software.

- Modern Utilities (WinZip, WinRAR, 7-Zip): Offer advanced features beyond basic OS support: stronger encryption (AES), support for multiple archive formats (RAR, 7z), archive splitting/spanning, self-extracting archives, repair capabilities, cloud integration.

- Alternative Formats: RAR (proprietary, good compression, popular), 7z (open source, often best compression via LZMA/LZMA2).

- Significance: Basic ZIP functionality became a standard OS feature, while dedicated utilities evolved to offer advanced capabilities and support for alternative formats, ensuring ZIP’s continued relevance alongside newer options.

Milestone Markers

- ~1998-2001: Microsoft integrates native ZIP support into Windows (Plus! 98, then Windows ME/XP).

- Early 2000s: Apple integrates ZIP support into Mac OS X.

- ~1999: 7-Zip first released, offering high compression ratios with its 7z format (LZMA).

- Late 2000s onward: Cloud storage services become popular, offering alternative ways to share large files. Dedicated ZIP utilities focus on power features and multi-format support.

Parallel Developments

- Mid-late 2000s: Widespread broadband adoption globally. Web 2.0 and social media mature.

- 2010s: Cloud storage becomes ubiquitous. Mobile devices become primary computing platforms for many. Internet speeds continue to increase dramatically (fiber optics).

User Experience Snapshot

Today, zipping files for an email attachment is often just a right-click -> “Send to Compressed folder” away. Extracting downloads is usually automatic or a simple double-click. It’s seamless. Yet, many still install WinRAR or 7-Zip for handling other archive types or needing features like password protection with strong encryption. While you might share large files via Google Drive link now instead of zipping, ZIP remains the reliable fallback, the format you know will just work for bundling things together.

Price Point Perspective

Basic ZIP functionality is now free, included with the OS. Advanced utilities like WinZip often use subscription models, while WinRAR maintains its perpetual shareware trial, and 7-Zip is completely free and open-source. The cost calculation has shifted from saving bandwidth/disk space to accessing specific advanced features or preferring a particular interface.

What We Gained / What We Lost

- Gained: Seamless, built-in support for basic ZIP operations. Powerful free options (7-Zip). Advanced features in dedicated utilities (strong encryption, multi-format support). Continued universal compatibility of the ZIP format.

- Lost: The necessity of dedicated software for simple tasks. Some user awareness of the underlying compression process as it became automated.

Unexpected Consequences

- The continued relevance of ZIP despite faster internet highlights the value of simple, universal standards for bundling and compatibility.

- Competition from free, high-performance formats like 7z keeps pressure on commercial developers.

- The legacy of Phil Katz remains intertwined with the format he created, a story of innovation, conflict, and personal tragedy.

Industry Voice

“ZIP is a standard type of format that any OS can enable. On the other hand, we need various supplementary tools to process any given RAR file format.” – BYJU’S GATE notes (Highlighting ZIP’s native support advantage). “7Z [often] takes first place with [compression ratio]…” “RAR is superior… because it’s not an open-source software with an excellent encryption algorithm.” – iSumsoft (Comparing formats).

Full Circle Reflections

From its fiery birth in the aftermath of the ARC vs. PKWARE legal battle, the ZIP file format embarked on an extraordinary journey. Driven by Phil Katz’s programming prowess and the crucial decision to release its specification openly, ZIP rapidly conquered the digital landscape. It became the indispensable tool that tamed the unwieldy files of the early computing era, making floppy disk storage practical and dial-up internet transfers bearable.

With the advent of graphical interfaces, tools like WinZip made its power accessible to everyone, cementing its status as the universal standard for file archiving and compression. It was the workhorse of the early internet, the invisible infrastructure enabling software distribution, email attachments, and web downloads.

Even today, in an age of multi-terabyte drives, gigabit internet, and seamless cloud storage, the humble ZIP file endures. Its integration into our operating systems speaks volumes about its foundational importance. While newer formats may offer better compression ratios and dedicated tools provide advanced features, ZIP remains the lingua franca of file bundling – simple, reliable, and universally understood. It stands as a testament to Phil Katz’s troubled genius and the enduring power of an efficient, open standard in shaping our digital world.

The Heritage Impact: Compressing the Digital Age

The history of ZIP files has profoundly impacted:

- File Storage & Transfer: Made efficient use of limited storage (floppies, early HDDs) and bandwidth (modems, early internet) possible.

- Software Distribution: Became the standard method for distributing shareware and downloading software online for decades.

- Internet Usability: Was critical infrastructure for the growth of email, FTP, and the World Wide Web.

- Operating Systems: Led to built-in compression features becoming standard in Windows and macOS.

- Open Standards: Demonstrated the power of a largely open specification in achieving widespread adoption and interoperability.

- Digital Literacy: Made file compression and archiving a basic, expected skill for computer users.

- Legal Landscape: The preceding ARC vs. PKWARE lawsuit highlighted early legal issues around software copyright and trademarks.

The ZIP file isn’t just a file format; it’s a silent facilitator, a piece of digital history that continues to serve a vital function in organizing and transmitting our data across the globe.

FAQ: Zipping Through the Facts

- Who invented the ZIP file format?

The .ZIP format and the original PKZIP utility were created by Phil Katz and his company PKWARE, Inc., released in 1989. Gary Conway of Infinity Design Concepts also contributed to the format design. - Why was the ZIP format created?

It was created after PKWARE lost a lawsuit brought by SEA, the creators of the competing ARC format. Phil Katz needed a new format to replace ARC for his popular compression utilities. He focused on speed and efficiency, and crucially, published the format’s specification. - Why is it called “ZIP”?

The name was suggested by Phil Katz’s friend, Robert Mahoney, to imply speed and efficiency – suggesting the software could “zip” through files quickly, faster than ARC. - Is the ZIP format still relevant today?

Absolutely. While faster internet and cloud storage have reduced the need for maximum compression in some cases, ZIP remains the most universally compatible archive format. It’s excellent for bundling multiple files together, widely used for email attachments, and supported natively by most operating systems, making it incredibly convenient and reliable. - What’s the main difference between ZIP, RAR, and 7z files?

- ZIP: Most compatible (supported natively by Windows/macOS), good compression (using DEFLATE usually), open specification.

- RAR: Proprietary format (requires WinRAR or compatible software), generally offers slightly better compression than standard ZIP, popular features like recovery records.

- 7z: Open source format (associated with 7-Zip utility), often achieves the highest compression ratios (using LZMA/LZMA2 algorithms), supports strong AES encryption.