Remember the panic? The sudden warning message, the system grinding to a halt. This chaos is central to the history of computer viruses. What began as experimental programs and floppy-disk annoyances evolved into the shadowy underbelly of our digital lives, from globe-spanning email worms to the costly ransomware of today.

Many of us remember specific outbreaks – the “ILOVEYOU” email that wasn’t a love letter, the Melissa virus that overloaded corporate servers, or perhaps even earlier scares like Michelangelo. These digital epidemics were more than just technical problems; they were cultural events that shaped our online behavior, fueled a multi-billion dollar cybersecurity industry, and served as stark reminders of our technology’s vulnerabilities [Google Search]. Let’s boot up the history files and trace the fascinating, and often frightening, evolution of computer viruses that went viral.

The Dawn of Digital Contagion: Early Experiments & Pranks

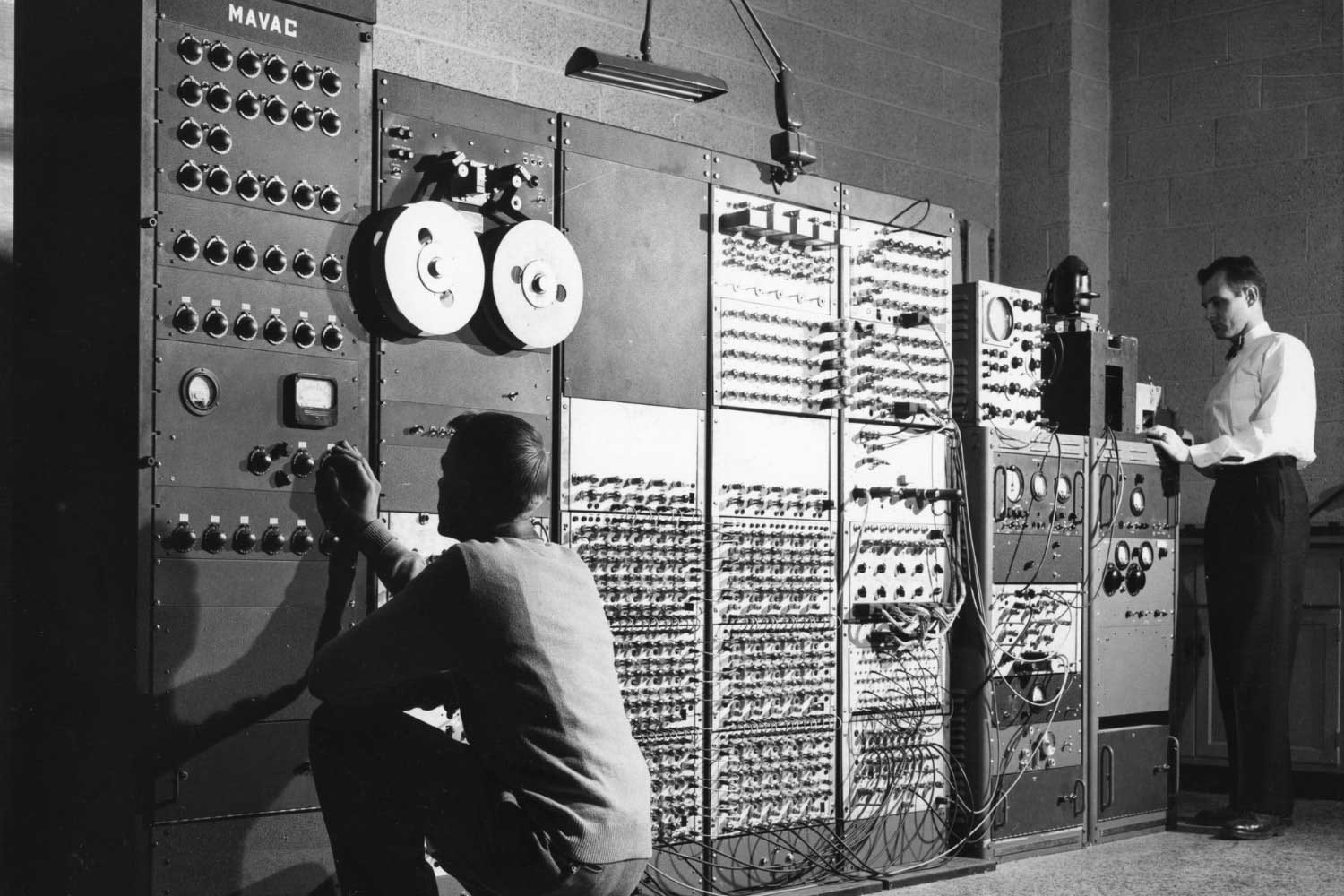

The idea of self-replicating programs predates personal computers. Mathematician John von Neumann theorized about “self-reproducing automata” back in the 1940s, laying the conceptual groundwork [Google Search]. But the first real glimpses emerged in the early days of networked computing:

- Creeper (1971): Often cited as the first experimental self-replicating program, Creeper was created by Bob Thomas at BBN Technologies [Google Search]. It moved between computers on the ARPANET (a precursor to the internet), displaying the message: “I’M THE CREEPER : CATCH ME IF YOU CAN” [Google Search]. It wasn’t malicious, more a proof of concept.

- Reaper (1972): Developed by Ray Tomlinson (inventor of email) in response to Creeper, Reaper was designed to find and delete Creeper instances – arguably the world’s first antivirus software [Google Search].

- Elk Cloner (1982): Created by 15-year-old Rich Skrenta as a prank on his friends, Elk Cloner was one of the first widespread personal computer viruses [Google Search]. It targeted Apple II systems, spreading via floppy disks. On every 50th boot from an infected disk, it displayed a short poem: “ELK CLONER: THE PROGRAM WITH A PERSONALITY…” [Google Search]. While mostly annoying, it could sometimes overwrite data.

- Brain (1986): Considered the first virus for IBM PCs (MS-DOS), Brain was created by two brothers in Pakistan, Basit and Amjad Farooq Alvi, ostensibly to track pirated copies of their medical software [Google Search]. It infected the boot sector of floppy disks and included the brothers’ contact information, leading to calls from infected users worldwide [Google Search].

These early examples were often experimental, proofs of concept, or pranks. Malicious intent wasn’t always the primary driver, but they demonstrated the potential for code to spread autonomously.

The Evolution of Epidemics: Viruses Go Mainstream & Malicious

As personal computing and networking grew in the late 80s and 90s, viruses evolved rapidly in sophistication and intent.

- The Morris Worm (1988): A watershed moment. Created by Cornell graduate student Robert Tappan Morris, this worm wasn’t intended to be destructive but spread rapidly across the early internet, exploiting vulnerabilities in Unix systems [Google Search]. It infected an estimated 10% of the internet (around 6,000 computers then), causing significant slowdowns and damage estimated in the millions [Google Search]. It highlighted the internet’s vulnerability and led to the creation of the first Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT).

- Michelangelo (1991): A DOS boot sector virus designed to activate only on March 6th (Michelangelo’s birthday) [Google Search]. On that date, it would overwrite critical parts of the hard drive. Media hype predicted massive damage, causing widespread panic, though the actual impact was less severe than feared [Google Search]. Still, it raised public awareness dramatically.

- Macro Viruses (Mid-90s): Viruses like Concept (1995) exploited the macro programming languages built into applications like Microsoft Word and Excel [Google Search]. They spread easily via document sharing.

- Melissa (1999): A devastating macro virus that marked a turning point. Spreading via email, it arrived as a Word document attachment, often with a subject like “Important Message From [Sender’s Name]” [Google Search]. When opened, it would email itself to the first 50 contacts in the user’s Outlook address book, causing massive email server overloads worldwide [Google Search]. Estimated damages were around $80 million, and its creator, David L. Smith, was caught and sentenced [Google Search].

- ILOVEYOU (2000): Perhaps the most infamous email worm. It arrived as an email with the subject “ILOVEYOU” and an attachment disguised as a love letter (LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.TXT.vbs) [Google Search]. Clicking it unleashed a script that overwrote files (including images and music) and mailed itself to the user’s entire Outlook contact list [Google Search]. It spread incredibly fast, infecting millions of computers globally, causing an estimated $5.5-$10 billion in damages and forcing major organizations like the Pentagon and CIA to shut down email systems.

- Code Red & Nimda (2001): These worms exploited vulnerabilities in Microsoft’s Internet Information Services (IIS) web server software [Google Search]. Code Red defaced websites and launched DDoS attacks; Nimda spread rapidly through multiple methods (email, network shares, web servers) causing widespread disruption [Google Search].

- SQL Slammer (2003): An incredibly fast-spreading worm targeting Microsoft SQL Server vulnerabilities. It infected an estimated 75,000 servers in just 10 minutes, significantly slowing global internet traffic [Google Search].

- Blaster (2003): Exploited a Windows vulnerability, causing infected computers to launch DDoS attacks against Microsoft’s update website and displaying popup messages [Google Search].

This era saw viruses evolve from floppy disk nuisances to sophisticated network worms capable of crippling global infrastructure and causing billions in economic damage.

“Technical” Specs: Malware Through the Ages

Let’s compare the typical characteristics of malware across different historical periods:

| Feature | Early Viruses (80s/Early 90s) | Macro/Email Worms (Mid 90s/Early 00s) | Early Trojans/Spyware (Early/Mid 00s) | Modern Ransomware/APTs (2010s-Present) |

| Primary Target | Boot Sectors, DOS Files | MS Office Docs, Email Clients (Outlook) | Windows OS, User Credentials | Filesystems, Networks, Critical Infra. |

| Propagation | Floppy Disks, Sneakernet | Email Attachments, Network Shares | Malicious Downloads, Drive-by exploits | Phishing, Exploits, RDP, Supply Chain |

| Payload | Annoyance (Messages, Slowdown), Minor Data Corruption | Data Deletion, Email Overload, Backdoors | Keystroke Logging, Info Theft, Botnet | File Encryption, Data Exfiltration, Sabotage |

| Motivation | Prank, Experiment, Piracy Control | Vandalism, Notoriety | Financial Gain (Banking Trojans) | Extortion, Espionage, Cyber Warfare |

| Complexity | Relatively Simple | More Complex (Scripting, Networking) | Stealth Techniques, Modular | Highly Sophisticated, Encrypted, Evasive |

| Mitigation | Early Antivirus, Disk Scanning | Antivirus, Email Filtering, Patching | Antivirus, Firewalls, User Ed. | Advanced Security Suites, Backups, Threat Intel, Zero Trust |

Export to Sheets

The evolution clearly shows a shift from relatively simple, often non-malicious programs to highly complex, financially motivated, and often state-sponsored cyber weapons.

Cultural Impact: From Annoyance to Existential Threat

The constant barrage of high-profile virus outbreaks profoundly impacted society and our relationship with technology.

- Loss of Innocence: The early, often playful viruses gave way to genuinely destructive and costly attacks, shattering the naive view of computers as inherently safe tools.

- Birth of an Industry: The rise of viruses directly fueled the growth of the multi-billion dollar antivirus and cybersecurity industry. Companies like Symantec (Norton) and McAfee became household names.

- Changed User Behavior: We learned (often the hard way) not to open attachments from strangers, to be wary of suspicious links, and the importance of software updates and backups. Cybersecurity awareness became a necessity.

- Media Hype & Fear: Major outbreaks like Michelangelo and ILOVEYOU generated intense media coverage, sometimes bordering on hysteria, further cementing viruses in the public consciousness.

- Legal & Ethical Frameworks: Outbreaks like the Morris Worm prompted the development of computer crime laws and ethical guidelines for computing professionals.

- Shift in Perception: Viruses evolved in the public eye from nuisances created by hobbyists or pranksters to serious threats orchestrated by organized crime or nation-states [Google Search].

The history of computer viruses is intertwined with the history of the internet itself, reflecting our growing dependence on digital systems and the increasing sophistication of those who seek to exploit them.

Collector’s Corner: Preserving Malware History (Safely!)

Collecting active malware is dangerous and illegal in many contexts. However, there’s a growing interest in preserving the history of malware and cybersecurity.

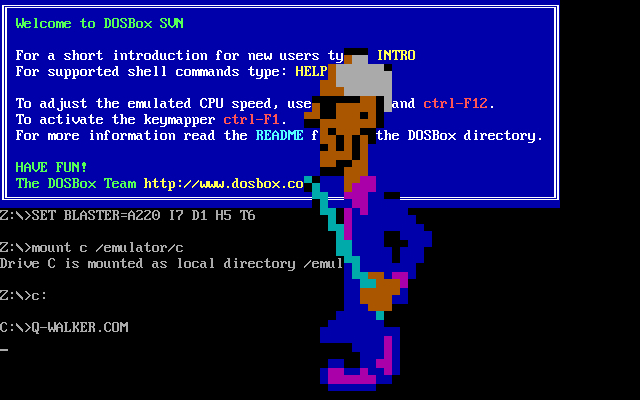

- The Malware Museum: Hosted by the Internet Archive, this project allows users to safely experience the visual effects of classic DOS viruses (like Cascade or Walker) within a browser-based emulator [Google Search]. The viruses have been neutered to remove their destructive routines [Google Search].

- Retro Antivirus Software: Original boxed copies of early antivirus software (like Norton AntiVirus, McAfee VirusScan from the 90s) are becoming collectible memorabilia, representing the dawn of the cybersecurity industry. Look for these on eBay or at vintage computer fairs.

- Books and Media: Books detailing famous hacks or the history of cybercrime (e.g., Clifford Stoll’s “The Cuckoo’s Egg” about early network intrusion) offer historical context. Documentaries about specific outbreaks also exist.

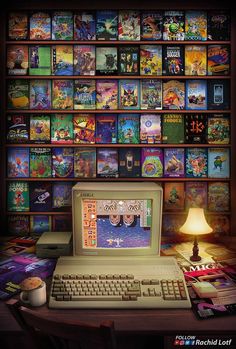

- Vintage Hardware: Running older operating systems like DOS or Windows 95 on period-correct hardware can provide a (sandboxed and offline!) environment to understand the context in which these early viruses operated.

It’s crucial to emphasize safety: never run old malware samples on connected or unprotected machines. Historical study should be done through safe, curated resources like the Malware Museum.

Why We “Miss” the Early Days (Sort Of)

It sounds strange to be nostalgic about computer viruses, given the damage they caused. But looking back, what aspects of that era contrast sharply with today’s threat landscape?

- Relative Simplicity: Early viruses, even destructive ones, were often less complex than modern threats like ransomware or state-sponsored APTs [Google Search]. The motivations sometimes felt more like digital graffiti or bragging rights than sophisticated extortion or espionage.

- Novelty and Understanding: There was a time when a virus spreading felt novel, almost like a strange natural phenomenon. While disruptive, the mechanics (e.g., a macro virus in Word) were sometimes easier for the average user to grasp than complex fileless malware or zero-day exploits.

- Clearer Boundaries: The threat often came via a specific vector – an infected floppy, an email attachment. Today, threats can come from compromised websites, malicious ads, IoT devices, or sophisticated phishing campaigns, making the attack surface feel much larger and more porous.

- Community Response: Major outbreaks often generated a sense of shared experience and community response, with users, tech support, and antivirus companies working together to understand and combat the threat. Today’s threats often feel more isolating and industrialized.

Nobody misses having their files deleted or their system crashing. But perhaps there’s a strange nostalgia for a time when the digital threats felt a bit less pervasive, less financially devastating, and perhaps, naively, a little less personal than today’s constant battles against ransomware and identity theft.

The Endless Arms Race: Malware’s Unending Evolution

The history of computer viruses is a relentless story of cat and mouse, an arms race between attackers and defenders that continues unabated. From the theoretical concepts of self-replication to the prankish Elk Cloner, the disruptive Morris Worm, the email-borne chaos of Melissa and ILOVEYOU, and onto the modern scourges of ransomware like CryptoLocker and WannaCry, malware has consistently adapted to exploit new technologies and human psychology [Google Search].

What began as experiments or vandalism has morphed into a sophisticated criminal enterprise and a tool of nation-states [Google Search]. The viruses that once spread via floppy disks now leverage global networks, social engineering, and complex evasion techniques. While our defenses have grown exponentially stronger, the fundamental battle remains: securing systems against code designed to breach them. Understanding this history isn’t just tech nostalgia; it’s crucial for appreciating the cybersecurity challenges we face today and the constant vigilance required to navigate our interconnected world safely.