Ah, the future—a shimmering horizon for innovators and dreamers. While predicting what’s next is an irresistible temptation, history is littered with the shattered remnants of failed tech predictions. These are the confident visions of tomorrow that… well, didn’t quite pan out, reminding us how difficult forecasting can be.

Sometimes spectacularly so. Let’s grab some popcorn, dust off the history books, and take a delightful, slightly embarrassing journey through some of tech’s most hilariously wrong predictions – moments when the future clearly had other plans.

The Computer Conundrum: Misjudging the Machine

It’s hard to imagine now, tethered as we are to devices in our pockets, desks, and laps, but there was a time when the very idea of personal computing seemed absurd to the experts.

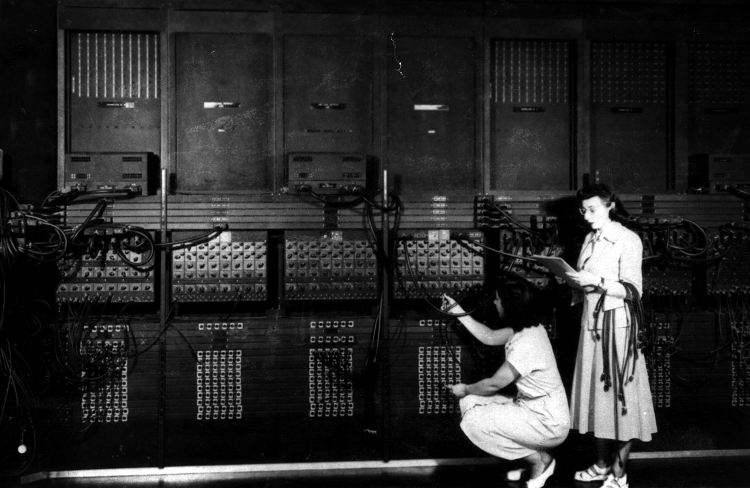

Crystal Ball Fail #1: The Five-Computer World?

- The Prediction: “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.”

- The Predictor: Attributed to Thomas Watson, President of IBM, 1943. (Note: The exact quote and attribution are debated, but reflect a common early sentiment about the scale of computing.)

- Context Corner: In the 1940s, computers were colossal, expensive, room-filling machines like ENIAC, primarily used for complex military or scientific calculations. The idea of mass production or individual ownership seemed fanciful. They were specialist tools for huge organizations.

- Reality Check: Fast forward to today. Billions of computers exist, not just on desks, but integrated into phones, cars, watches, refrigerators… Watson (or whoever said it) might have underestimated the market by a few billion percent. Oops.

- Hindsight is 20/20: The failure here was an inability to foresee miniaturization, dramatic cost reduction, and the explosion of applications beyond mere calculation. They saw computers as calculators, not platforms for communication, creativity, and commerce.

Crystal Ball Fail #2: No Room for Home Computers

- The Prediction: “There is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home.”

- The Predictor: Ken Olsen, Founder and President of Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), 1977.

- Context Corner: DEC was a giant in the minicomputer market, selling powerful machines to businesses and labs. Olsen was likely thinking about computers for complex data processing or automation, not for writing letters, playing games, or (gasp!) going online – things home PCs would eventually excel at. His frame of reference was the business utility of computers as he knew them.

- Reality Check: By 2009, roughly 80% of US households had at least one computer. Today, home computers are central to work, education, entertainment, and communication. You’re likely reading this on one right now. DEC, meanwhile, struggled to adapt to the PC revolution and was acquired by Compaq in 1998.

- Amusement Factor: Imagine Olsen walking into a modern home office or seeing a kid doing homework on a laptop. The sheer ubiquity of home computing would likely boggle his 1977 mind.

Crystal Ball Fail #3: 640K Should Be Enough…

- The Prediction: “640K [of memory] ought to be enough for anybody.”

- The Predictor: Widely misattributed to Bill Gates, 1981. While Gates has denied saying this exact phrase, it captures the sentiment of the era regarding early PC memory limitations.

- Context Corner: Early IBM PCs were limited to 640 kilobytes of RAM by their architecture. At the time, this seemed like a generous amount compared to predecessors. Software was simpler, graphical interfaces were nascent, and multimedia was science fiction.

- Reality Check: Modern operating systems and applications require gigabytes of RAM – thousands of times more than 640K. Even a basic smartphone today typically has 4GB (over 6,500 times more) or 8GB (over 13,000 times more) of RAM. The idea of 640K being sufficient is laughably inadequate.

- Hindsight is 20/20: This reflects a failure to anticipate the exponential growth of software complexity, graphical user interfaces, multitasking, and data-intensive applications.

The Internet Illusion: Doubting the Digital Deluge

The World Wide Web. The Information Superhighway. Call it what you will, but its rise wasn’t universally foreseen. Some very smart people looked at the fledgling network and saw… not much.

Crystal Ball Fail #4: The Great Internet Collapse of ’96

- The Prediction: “I predict the Internet will soon go spectacularly supernova and in 1996 catastrophically collapse.”

- The Predictor: Robert Metcalfe, co-inventor of Ethernet and founder of 3Com, 1995.

- Context Corner: Metcalfe worried that the internet’s infrastructure couldn’t handle its rapid, exponential growth. He cited concerns about bandwidth, scalability, security, and viable business models. Dial-up was slow, connections were flaky – his concerns weren’t entirely unfounded at that moment.

- Reality Check: 1996 came and went. The internet did not collapse. It boomed. Metcalfe, to his credit, famously blended a copy of his prediction column and drank it at a conference in 1997.

- Amusement Factor: Metcalfe, a key figure in networking technology, betting against the ultimate network! The irony is delicious. His willingness to literally eat his words earns him points, though.

Crystal Ball Fail #5: E-Commerce? Nah.

- The Prediction: “Remote shopping, while entirely feasible, will flop—because women like to get out of the house, like to handle the merchandise, like to be able to change their minds.”

- The Predictor: TIME Magazine, in a 1966 essay titled “The Futurists.”

- Context Corner: This was written long before the internet as we know it, likely envisioning catalog phone orders or primitive video links. The reasoning reflects the social norms and shopping habits of the 1960s, failing to account for convenience, changing lifestyles, and, well, sexism.

- Reality Check: Global e-commerce sales are measured in the trillions of dollars annually. Amazon, Alibaba, Shopify, and countless others thrive. Apparently, people (of all genders!) quite like the convenience of remote shopping.

- Hindsight is 20/20: A classic case of projecting current social behaviors onto future technology, failing to see how the tech itself could change those behaviors.

Crystal Ball Fail #6: No Better Than a Fax Machine

- The Prediction: “The growth of the Internet will slow drastically… By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.”

- The Predictor: Paul Krugman, Nobel laureate economist, 1998.

- Context Corner: In 1998, the dot-com bubble was inflating, but the internet’s true transformative power across industries wasn’t fully apparent to everyone. Krugman questioned the network’s long-term economic significance compared to established technologies.

- Reality Check: The internet has fundamentally reshaped global commerce, communication, media, entertainment, finance, and nearly every other aspect of the economy. Comparing its impact to the fax machine seems… quaint.

- Pundit Scorecard: Even Nobel Prize winners can whiff it when predicting tech’s trajectory.

Communication Catastrophes: Missing the Call

Connecting the world hasn’t always seemed like a good bet. Some of the most revolutionary communication tools faced early skepticism.

Crystal Ball Fail #7: The Telephone’s “Shortcomings”

- The Prediction: “This ‘telephone’ has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication.”

- The Predictor: Internal Western Union memo, 1876. (Often attributed to President William Orton).

- Context Corner: Western Union was the king of the telegraph – a proven, profitable technology. The early telephone was experimental, expensive, and limited in range and clarity. From WU’s perspective, it likely seemed like an unreliable toy compared to their established network.

- Reality Check: Alexander Graham Bell offered to sell his patent to Western Union for $100,000. They declined. Bell Telephone Company was formed, and the rest is history. Western Union later tried to launch its own competing phone service, leading to patent battles it ultimately lost.

- Amusement Factor: Imagine being the executive who passed on the telephone because it wasn’t as good as the telegraph. That’s a resume line you probably leave off.

Crystal Ball Fail #8: The iPhone? No Chance.

- The Prediction: “There’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. No chance.”

- The Predictor: Steve Ballmer, Microsoft CEO, 2007.

- Context Corner: Microsoft dominated the PC market and had its own Windows Mobile platform for smartphones (which were typically business-focused, often with physical keyboards). Ballmer scoffed at the iPhone’s high price (relative to subsidized competitors), lack of a physical keyboard (“not a very good email machine”), and Apple’s closed ecosystem. He saw it as a niche luxury product.

- Reality Check: The iPhone revolutionized the entire mobile industry, popularized the touchscreen interface, kickstarted the app economy, and became one of the best-selling consumer electronics products in history. Microsoft struggled for years to gain traction in the modern smartphone market.

- Hindsight is 20/20: Ballmer viewed the iPhone through the lens of the existing smartphone market (business users, physical keyboards, carrier control) rather than seeing its potential to create a new market centered on user experience, apps, and media consumption.

Media Mix-ups & More: Underestimating Entertainment and Invention

It wasn’t just computers and communication; predictions about entertainment, travel, and basic science also produced some gems.

Crystal Ball Fail #9: Silence is Golden?

- The Prediction: “Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?”

- The Predictor: Harry M. Warner, President of Warner Brothers Pictures, circa 1927.

- Context Corner: Silent films were a mature, globally successful art form and business. Adding synchronized sound (“talkies”) was technically complex, expensive, and risked alienating audiences accustomed to the established format (and international audiences who wouldn’t understand English dialogue).

- Reality Check: Warner Bros. took a gamble on sound with The Jazz Singer (1927). Its success ushered in the era of talking pictures, fundamentally changing cinema forever. Silent films rapidly became obsolete.

- Amusement Factor: The head of a major movie studio questioning the appeal of audible dialogue!

Crystal Ball Fail #10: The Horseless Carriage Fad

- The Prediction: “The horse is here to stay, but the automobile is only a novelty—a fad.”

- The Predictor: The President of the Michigan Savings Bank, advising Henry Ford’s lawyer Horace Rackham not to invest more in Ford Motor Company, 1903.

- Context Corner: Early automobiles were expensive, unreliable, required difficult maintenance, and lacked infrastructure (paved roads, gas stations). Horses were the established, universal mode of transport. The banker compared cars to the bicycle craze, suggesting the novelty would wear off.

- Reality Check: Ford perfected mass production, making cars affordable. Roads were paved. Gas stations proliferated. The horse-drawn era ended. Rackham ignored the advice, invested heavily, and became fabulously wealthy. The banker… not so much.

- Hindsight is 20/20: Underestimating the power of mass production, infrastructure development, and the sheer human desire for faster, more personal transportation.

Why So Wrong? The Perils of Prediction

Looking back, it’s easy to laugh. But why do predictions, especially about technology, go wrong so often?

- Linear Thinking: Extrapolating the present linearly into the future, failing to account for exponential growth or disruptive leaps (like Moore’s Law or the invention of the transistor).

- Incumbent Blinders: Existing industry leaders often view new tech through the lens of their current business model, dismissing threats or opportunities that don’t fit (Western Union vs. telephone, Microsoft vs. iPhone).

- Ignoring User Desire: Focusing purely on technical specs or business models without considering how technology might fulfill latent consumer needs or desires (home computers, online shopping).

- Underestimating Infrastructure & Ecosystems: Failing to see how related developments (better networks, cheaper components, app stores) can unlock a technology’s potential.

- Lack of Humility: Overconfidence in one’s own expertise and an unwillingness to admit the inherent uncertainty of the future.

A Grain of Salt for Today’s Forecasts

This trip down memory lane isn’t just for amusement. It’s a potent reminder to approach today’s bold tech predictions with healthy skepticism. Will AI truly achieve general intelligence by 2030? Will the Metaverse replace the office? Will quantum computing change everything overnight? Maybe. Maybe not.

The future often refuses to cooperate with our neat projections. It zigs when we expect it to zag. But that unpredictability is also what makes technology so exciting. The next “hilariously wrong” prediction might be simmering right now, waiting for reality to deliver the punchline.

FAQ: Failed Futures Edition

- What’s the most famously wrong tech prediction?

It’s subjective, but contenders include Ken Olsen dismissing home computers, Western Union snubbing the telephone, Steve Ballmer laughing off the iPhone, and Thomas Watson’s “five computers” estimate. - Why are experts often wrong about future technology?

Experts can be hampered by their deep knowledge of the current paradigm, making it hard to imagine truly disruptive shifts. They might focus on technical limitations of the present or be biased by their company’s existing interests. - Did Bill Gates really say “640K ought to be enough for anybody”?

He has consistently denied saying this exact quote, and no definitive source confirms it. However, it accurately reflects the limited perspective on memory needs during the very early days of personal computing around 1981. - Are any tech predictions accurate?

Absolutely! Gordon Moore’s prediction about transistor density (Moore’s Law) held remarkably true for decades. Science fiction writers like Arthur C. Clarke accurately predicted communication satellites. Success often comes from understanding underlying trends rather than specific products. - Should we ignore all tech predictions?

No, but view them critically. Understand the predictor’s biases and assumptions. Look for predictions based on fundamental trends versus hype. Use them as thought-starters, not infallible roadmaps.